World War II career

Stark was appointed as the Chief of Naval Operations, with the rank of Admiral, in August of 1939 by Franklin D. Roosevelt (Naval History and Heritage Command). As CNO, Stark was the principal to the Secretary of the Navy, consulting on matters of war and operations of the navy. He was responsible for the command of effective naval use, as well as allocation and use of resources for Navy shore activities (United States Navy). Stark had recognized the Navy was not ready for war and with the president's approval spearheaded the creation of the Two Ocean Navy Act. This act would strengthen the naval force, establishing a larger enough fleet that could defend both the country’s interests on both the Atlantic and Pacific shorelines (World War II Database).

With Admirals Ernest King and Harold Stark in the background, FDR sits with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill following church services during the Atlantic Charter meeting. Over the previous year, Roosevelt had greatly expanded the size of the U.S. Navy while providing naval assistance to beleaguered Britain.

Sourced: National Archives; U.S. Naval Institute; ca 1941; ACD 2025

It was passed in Congress in July 1940, and provided more than 1.3 million tons of new construction, 70% expansion of the U.S Navy. During his command, Stark would oversee significant naval expansion during 1940-1941, negotiating a period of “undeclared war against German submarines,” and increasing military preparedness, including “neutrality patrols” with German submarines in the Atlantic (Naval History and Heritage Command).

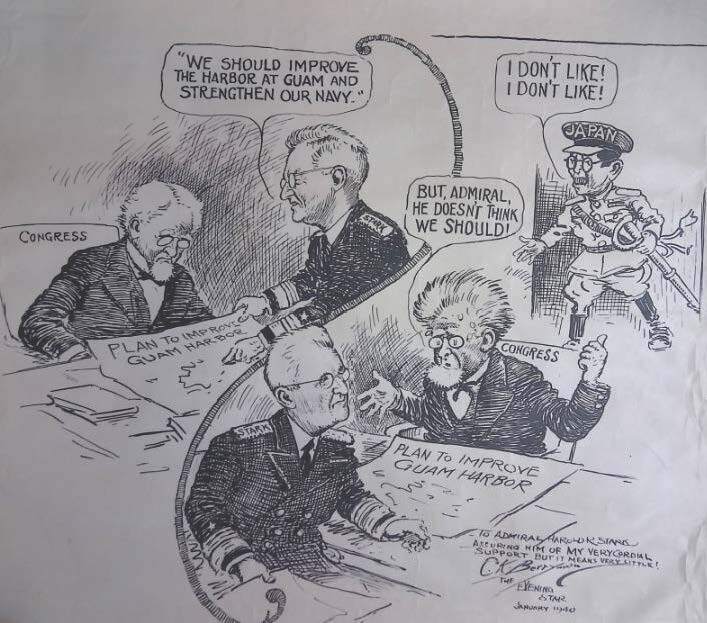

Below is a January 1940 political cartoon from the Evening Star by Clifford K. Berryman who is highlighting Stark's proposals to strengthen the U.S. Navy with Emperor Hirohito's disapproval.

Early in his career, Stark had established a reputation as a strict, but fair officer. It was said that his ships were “taut” environments, but “happy” for the level of performance onboard under his command (Harold Stark Biography). The Stark collection at Wilkes University contains numerous connections of Stark’s professional relationships, where we can see the appreciation of his friendship as much as his command, (1937-1943):

Photograph of Robert C. Giffen with Message and Signature, 1942 June 7

Photograph of Admiral Andrew Cunningham of the Royal Navy with Message and Original Signature

Photograph of General Henry H. Arnold with Message and Original Signature

Photograph of Lewis Compton With Note and Signature

Photograph of Lieutenant General John C. H. Lee with Message and Original Signature

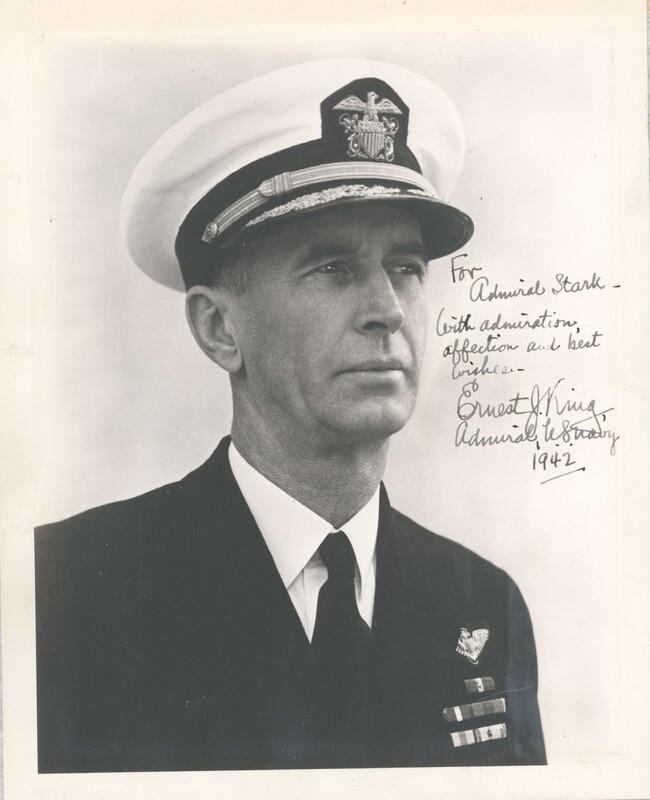

Photograph of Admiral Ernest J. King with Message and Original Signature

Photograph of Admiral Ben Moreell with Message and Original Signature, 1942 March 17

Photograph of Royal Navy Officer Geoffrey Blake standing on the Deck of the HMS Hood with Signature, 1937

Photograph of Former U.S. Secretary of Navy Charles Edison with Message and Signature, 1940 November 5

Photograph of Nancy Dill with messages and signatures, 1943 January

Photograph of John Greer Dill with messages and signatures, 1943 January

Stark helped create the Combined Chiefs of Staff to coordinate Anglo-American strategy and his command embraced all U.S naval forces assigned to British waters and in the Atlantic coastal waters of Europe.

Admiral Harold Stark speaks at commissioning of USS North Carolina (BB-55) on 9 Apr 1941. Sourced: Naval History and Heritage Command, ACD May 2025.

Though he had many favorable outcomes under his service, his career is largely marked by a controversy related to his handling of a decisive conflict during World War II: the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Once the U.S entered the war, the U.S Navy was at war against Germany in the Atlantic to support Great Britain. Stark believed Germany posed greater danger, and opposed any action that would have provoked the Japanese military. While American cryptologists had been attentive to any sensitive diplomatic correspondence coming from Japan to keep Roosevelt informed of their political moves, the information on Japanese military plans were classified to Japanese Naval communications, whose ciphers and codes were largely resistant to American cryptologists (NSA/CSS).

A typical Enigma intercept from the Bletchley Park operation in England formed from parts of two messages to the German Army Group Courland (Kurland) on Feb. 14, 1945. These messages were transmitted in Morse code as groups of five letters, which were easily intercepted -- but were impossible to understand without sophisticated decryption. Sourced: National Museum of the United States Air Force.

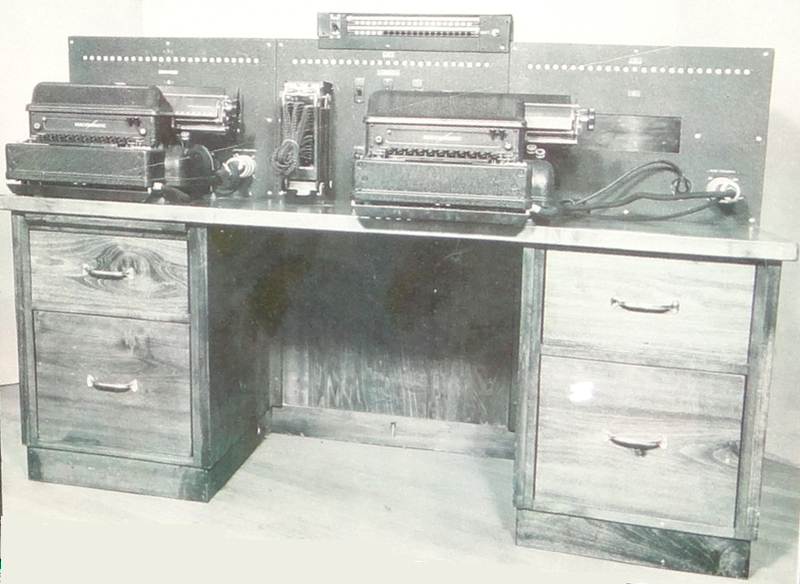

Analog of the Japanese Type B Cipher Machine (codenamed Purple) built by the U.S. Army Signal Intelligence Service. Wikipedia, orig. sourced National Cryptologic Museum; ACD 2025

While all agencies sought to place responsibility for the attack, it is not surprising to find that the culpability was leveled on many of the “area commanders, General Walter Short, USA, and Admiral Husband Kimmel, USN,” while those officials in Washington were “exonerated” (NSA). As the tension came down on Kimmel, the lens of critique shifted to Stark who was thought to have not properly informed Kimmel of how critical the situation was prior to the attacks on Pearl Harbor. He became an easy target, as he oversaw all combat operations against Japan with his recent promotion to CNO that year.

Stark would face a Court of Inquiry to consider his actions leading up to the attack, with evidence being brought forth to James Forrestal, the Secretary of the Navy. Even though the court displayed that the army and navy had responded adequately to the attack, whose loss was decisive due to an unpredictable weapon, the aerial torpedo, Forrestal denounced these findings, stating that the Kimmel and Stark “failed to demonstrate the superior judgment necessary for exercising command commensurate with their rank and their assigned duties" (Pearl Harbor Attack Hearings).

In March 1942, Stark was relieved of his position as CNO and was sent to England to remain on active duty as Commander forces for the Europe based U.S navy. Stark would be succeeded by Ernest J. King in March of 1942, who played a key role in Stark’s controversy by aligning with Kimmel’s criticism of Stark to Forrestal.

In later years, King would retract his condemning words and ask that the endorsement be expunged from the record. A biographer, Thomas Buell, quotes King in his work, Master of Sea Power, where King states that it was the “only time [he] admitted he had been wrong.”

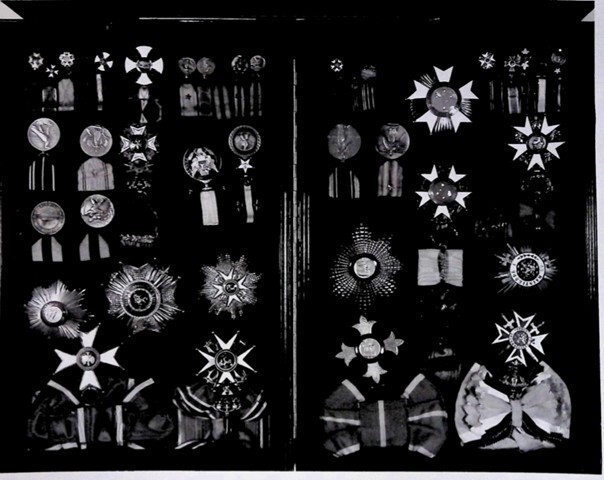

Admiral Stark had received various awards and decorations throughout his World War II military career, some including: Distinguished Service U.S Navy, American Defense Service Medal, French Legion of Honor, and American Defense Service Medal. One of the most significant being his Grand Cross Ribbon award. The award is bestowed upon officers who have demonstrated outstanding leadership and bravery in combat or other military operations.

His efforts to strengthen the U.S. Navy before the nation's entry into World War II proved vital to the Allied war effort, and his contributions to the strategy between the United States and Great Britain left a lasting impact on military cooperation. Despite facing criticism for the events surrounding Pearl Harbor, Stark’s leadership in Europe and his many commendations speak to the respect he earned from both American and Allied forces.